In the 1980s, Japan’s economy epitomized success. Tokyo, with its neon-lit skyscrapers and bustling districts like Ginza and Roppongi, symbolized a nation at the peak of prosperity. The post-war period saw Japan transform from a war-torn country into a global economic powerhouse, a period often referred to as the Japanese Miracle. This transformation was marked by a staggering 435% economic growth between 1955 and 1975, making Japan the second-largest economy in the world, trailing only behind the United States.

The Ingredients of the Japanese Miracle

U.S. Support and Economic Strategy

Post-World War II, the United States aimed to showcase the success of capitalism in Asia, choosing Japan as its focal point. By setting the yen at a low exchange rate against the dollar in 1949, the U.S. made Japanese goods extremely competitive in the American market, inadvertently setting the stage for Japan’s export boom. This economic strategy, known as the “Yoshida Doctrine,” emphasized economic recovery over military spending and laid the foundation for Japan’s future growth.

Industrial Policies and Keiretsu System

Japan’s industrial policies focused on heavy industries like shipbuilding, electric power, coal, and steel. The keiretsu system, a network of interlinked businesses that share resources and support each other, played a significant role. This system allowed companies to pool resources and expertise, fostering a cooperative business environment. Major keiretsu groups like Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Sumitomo dominated the economy, providing stability and facilitating coordinated economic activity.

Bank of Japan’s Window Guidance

The Bank of Japan’s policy of “window guidance” encouraged commercial banks to lend money to key sectors, fueling industrial growth. This policy helped ramp up production and investment, driving the economy forward. The central bank’s directive was pivotal in ensuring that credit flowed into strategic industries, promoting rapid industrialization and technological advancement.

Focus on Exports

Japan’s strategy of focusing on exports paid off handsomely. The 1964 Tokyo Olympics provided a perfect stage to showcase Japan’s industrial prowess to the world, boosting its international trade. Japanese products became renowned for their quality and innovation, with brands like Toyota, Sony, and Honda gaining global recognition. The country’s trade surplus soared, solidifying its position as an export-driven economy.

The Bubble Years

By the 1980s, Japan had cemented its status as an economic juggernaut. Japanese products, once considered cheap novelties, were now synonymous with high quality and innovation. Brands like Toyota, Sony, Nissan, and Mitsubishi became global household names. The real estate and stock markets saw unprecedented growth, fueled by cheap credit and speculative investments.

The Plaza Accord and Its Consequences

In 1985, the Plaza Accord was signed by officials from the G5 nations – France, Germany, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan. The agreement aimed to depreciate the US dollar relative to the yen and the German Deutsche Mark. Japan agreed to this deal under significant pressure from its Western allies, particularly the United States, which was grappling with a massive trade deficit.

The value of the yen skyrocketed, making Japanese exports more expensive and less competitive abroad. In response, the Bank of Japan implemented drastic measures to counteract the economic slowdown, slashing interest rates from 5% to 2.5%, the lowest in the industrialized world. The goal was to stimulate domestic demand and offset the negative impact on exports. However, this led to unintended consequences.

The Bubble Economy

With money now incredibly cheap to borrow, a speculative frenzy ensued. Investors poured money into the real estate market, causing land prices to skyrocket. Tokyo’s real estate market became one of the most expensive in the world. Even small plots of land in the city were valued at astronomical prices. The speculation wasn’t limited to real estate; it extended to the stock market as well.

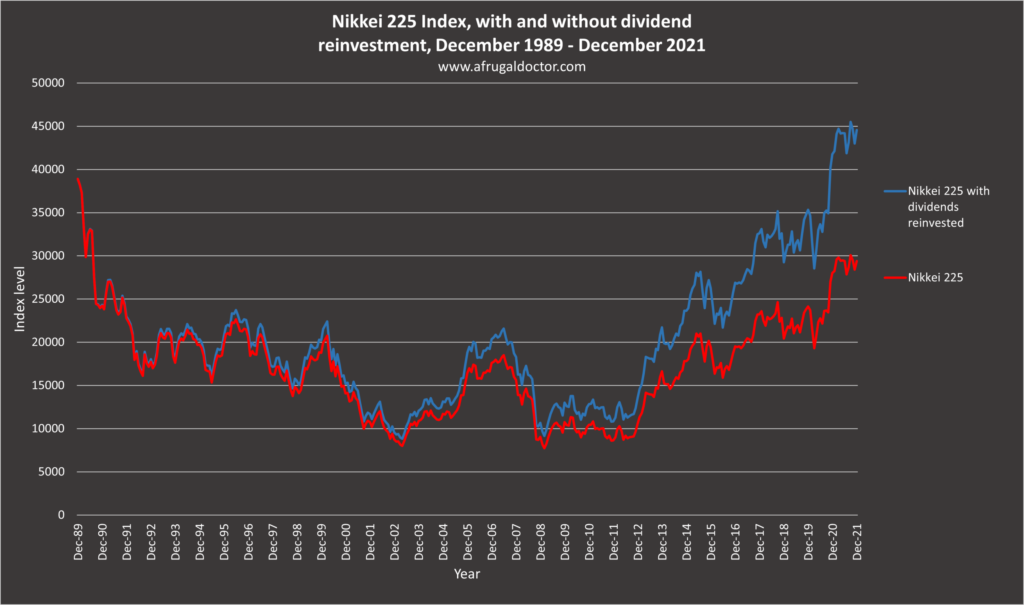

Between 1985 and 1989, stock prices surged by 240%, while land prices increased by 245%. The Nikkei 225 index, a benchmark for the Tokyo Stock Exchange, soared to record highs. Companies exploited accounting practices that allowed them to inflate their profits by reflecting the increasing value of their land holdings. This artificial boost in wealth further fueled speculative investments.

Corporate Speculation and Extravagance

Japanese corporations, flush with cash and rising stock values, engaged in speculative investments rather than focusing on their core businesses. Nissan, for example, earned more from real estate and financial speculation than from selling cars. Companies bought golf club memberships for millions of dollars, treating them as valuable assets.

The bubble era’s extravagance was epitomized by Japan’s global shopping spree. Mitsubishi Estate purchased New York’s Rockefeller Center, and Sony acquired Columbia Pictures. In 1986, Japan bought 75% of the US government bonds for sale. The country’s economic might seemed unstoppable.

The Crash

The speculative bubble reached its peak by the late 1980s. Real estate and stock prices soared to unsustainable levels. When the Bank of Japan finally took measures to cool the overheated economy by raising interest rates and capping real estate loans, the bubble burst. The stock market plummeted, and real estate values collapsed, leading to widespread financial turmoil.

Between 1990 and 2003, Japan faced severe economic stagnation, a period now known as the Lost Decades. Over 212,000 businesses went bankrupt, millions lost their jobs, and the stock market lost 80% of its value. The economic downturn led to a societal shift, with rising unemployment, increased social withdrawal (hikikomori), and declining birth rates.

The Lost Decades

The Aftermath of the Bubble Burst

The aftermath of the bubble burst was devastating. The economic stagnation lasted for more than a decade, leading to what is now referred to as Japan’s Lost Decades. During this period, Japan’s GDP growth averaged a mere 1.14% annually. The stock market’s decline wiped out trillions of dollars in wealth, and the real estate market collapsed, leaving many with properties worth far less than their mortgages.

Unemployment soared, and the traditional lifetime employment system crumbled. Major corporations like Mazda were forced to undergo restructuring, often with the help of foreign executives. Ford took over Mazda and implemented significant workforce reductions. This marked a cultural shift, as job security, once a cornerstone of Japanese corporate culture, became uncertain.

Societal Impact

The economic stagnation had profound effects on Japanese society. The younger generation, facing limited job prospects and financial insecurity, experienced immense pressure. This led to a rise in social withdrawal (hikikomori), where individuals retreat from social life, often confining themselves to their rooms for months or even years. The number of hikikomori has grown significantly, with an estimated 1.15 million people affected as of 2020.

The birth rate also declined sharply. In 2023, Japan recorded its lowest number of newborns ever, with only 758,000 births, a 5.1% decrease from the previous year. Many young people cited economic pressures and high living costs as reasons for delaying or forgoing marriage and children. This demographic shift has resulted in a rapidly aging population, with significant implications for Japan’s future.

Structural Reforms and Government Response

Fiscal Stimulus and Public Works

The Japanese government and financial institutions attempted various measures to counteract the prolonged economic stagnation. The government initiated a series of fiscal stimulus packages throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, focusing on public works projects to stimulate the economy. While these measures provided temporary boosts, they also led to a significant increase in public debt without addressing underlying structural issues.

Monetary Easing and Quantitative Easing

The Bank of Japan implemented monetary easing policies, including lowering interest rates to near zero and later adopting quantitative easing (QE) measures. These steps aimed to increase liquidity and encourage lending, but the impact was limited by persistent deflationary pressures and weak consumer demand.

Banking Sector Reforms

Efforts were made to clean up the banking sector, which was burdened with non-performing loans (NPLs). The Financial Reconstruction Law of 1998 enabled the government to inject capital into banks and take over insolvent institutions. This helped stabilize the banking system, but the recovery was slow and gradual.

Corporate Restructuring and Deregulation

Companies were encouraged to restructure and become more competitive. Deregulation in various sectors aimed to reduce barriers to entry and promote innovation. However, deeply entrenched corporate practices and resistance to change often hampered these efforts.

The Long-Term Impact

Japan’s economic stagnation had profound effects on its society and global standing. Once home to 32 of the world’s top 50 companies by market cap in 1989, Japan today has only one company, Toyota, in the top 50. The nation faced significant challenges, including an aging population, low birth rates, and mounting national debt.

Efforts to rejuvenate the economy, such as the adoption of new economic policies and attempts to stimulate innovation, have had mixed results. The rigid structures that once propelled Japan to economic greatness became obstacles in the face of rapid global changes.

Lessons for the Future

Japan’s economic journey serves as a cautionary tale for other nations. The euphoria of rapid economic growth can lead to reckless financial behavior and speculative bubbles. Effective regulation, prudent economic policies, and adaptability are crucial in sustaining long-term economic health.

The rise and fall of Japan’s economy in the 1980s remind us of the delicate balance required in economic management. While Japan remains a significant global player, its experience underscores the importance of learning from past mistakes to build a resilient and sustainable economic future.

Conclusion

The Japanese economic miracle of the 1980s, followed by the dramatic burst of its bubble, provides a compelling narrative of rapid growth and severe consequences. The lessons from Japan’s experience highlight the need for balanced economic policies, vigilant regulatory oversight, and the ability to adapt to changing global dynamics. As nations around the world navigate their own economic challenges, the story of Japan’s rise and fall remains a valuable guide in the pursuit of sustainable prosperity.